Doggerland, now submerged beneath the North Sea, connected Britain to continental Europe around 11,000 years ago.

The term is derived from the Dogger Bank, a shallow area in the North Sea where fishermen often find the remains of prehistoric animals and artefacts.

Doggerland was inhabited by Mesolithic people and was likely a rich environment supporting a variety of wildlife and human populations.

As woodlands and other flora flourished so did the range of mammals; fish and birds supported Mesolithic communities and populated some of the richest hunting and fishing grounds in Europe.

As sea levels rose after the last Ice Age, Doggerland gradually submerged beneath the waters of the North Sea, eventually becoming the seafloor we see today.

The study of Doggerland provides valuable insights into prehistoric human migration patterns and the effects of climate change on ancient landscapes.

More than 10,000 years ago, during the last ice age, sea levels were much lower than they are today.

Much of the world’s water was locked up in massive ice sheets, and what is now the North Sea was dry land.

This area, known as Doggerland, was home to ancient humans, animals, and ecosystems.

It stretched from the east coast of England to the Netherlands and Denmark, covering an area roughly the size of present-day Great Britain.

Doggerland was not just a barren landscape; it was teeming with life.

Archaeological evidence suggests that it was inhabited by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer communities who relied on the rich resources of the land and sea for their survival.

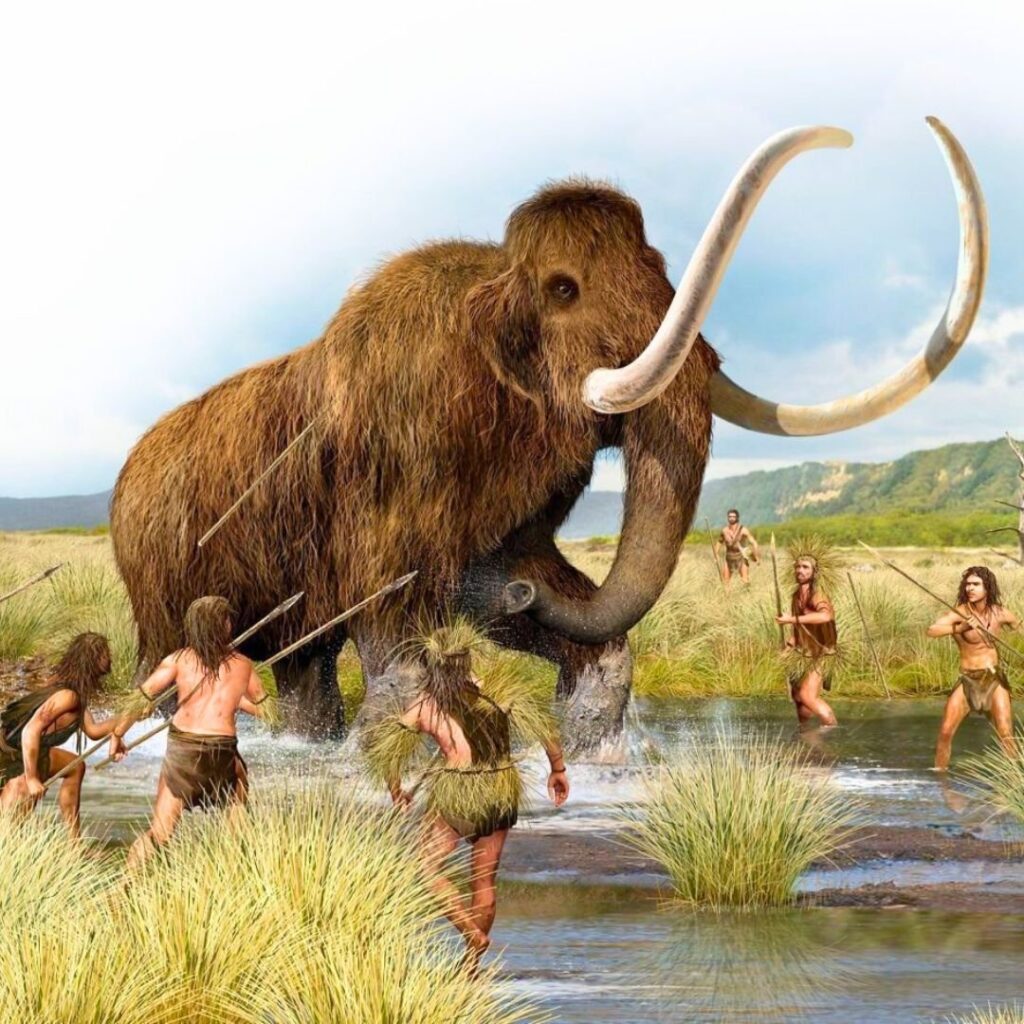

They would have hunted animals like red deer, wild boar, and even mammoths, as well as gathering shellfish and other marine resources along the coastline.

But around 8,000 years ago, as the Earth’s climate warmed and the ice sheets began to melt, sea levels rose rapidly, submerging Doggerland beneath the waters of the North Sea.

The once-thriving landscape disappeared beneath the waves, leaving behind only scattered remnants and tantalising clues for modern researchers.

A recent hypothesis suggests that around 6200 BCE much of the remaining coastal land was flooded by a tsunami caused by a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway known as the Storegga Slide.

This suggests “that the Storegga Slide tsunami would have had a catastrophic impact on the contemporary coastal Mesolithic population.

Britain finally became separated from the continent and in cultural terms, the Mesolithic there goes its own way.”

It is estimated that up to a quarter of the Mesolithic population of Britain lost their lives.

A study published in 2014 suggested that the only remaining parts of Doggerland at the time of the Storegga Slide were low-lying islands, but supported the view that the area had been abandoned at about the same time as the tsunamis.

Discoveries made

In 1931, the trawler Colinda hauled up a lump of peat whilst fishing near the Ower Bank, 40 km (25 mi) east of Norfolk.

The peat was found to contain a barbed antler point, possibly used as a harpoon or fish spear, 220 mm (8.5 in) long, which dated from between 10,000 and 4,000 BCE when the area was tundra.

Interest was reinvigorated in the 1990s by Bryony Coles, who named the area “Doggerland” “after the great banks in the southern North Sea” – and produced speculative maps of the area.

Although she recognised that the current relief of the southern North Sea seabed is not a sound guide to the topography of Doggerland, this topography has more recently begun to be reconstructed more authoritatively using seismic survey data obtained from oil exploration.

A skull fragment of a Neanderthal, dated at over 40,000 years old, was recovered from material dredged from the Middeldiep, some 16 km (10 mi) off the coast of Zealand, and exhibited in Leiden in 2009.

In March 2010, it was reported that recognition of the potential archaeological importance of the area could affect the future development of offshore wind farms.

In 2019, a flint flake partially covered in birch bark tar dredged up off the coast of the Netherlands provided valuable insight into Neanderthal technology and cognitive evolution.

Mammoths in Doggerland

Famously, the legendary Mammoths once roamed Doggerland.

A full-grown woolly mammoth, just one species of the genus Mammuthus, stood 10-12 feet at the shoulder with shaggy hair.

This hair provided a substantial advantage in the struggle to stay warm.

Roughly the mass of a modern African elephant, the woolly mammoth evolved some 400,000 years ago in Siberia from the steppe mammoth widespread on that continent, and ultimately spread westward into Europe.

This event may have been the second mammoth migration of the New World, as the steppe mammoth forayed into North America about 1.5 million years ago and evolved there into the endemic (and enormous) Columbian mammoth.

Mammoths were an important food source to early humans and neanderthals.

They even used their bones and hides to create huts and other structures.

Along with a shifting climate, it was this predation by humans that would ultimately drive the mammoth into extinction.

Our Neanderthal Relatives: Britain’s Ancient Inhabitants

These early hominins, who lived in Europe and parts of Asia for hundreds of thousands of years, left behind a legacy that continues to intrigue scientists and archaeologists to this day.

And while much of our knowledge about Neanderthals comes from sites on the continent, recent discoveries have shed new light on their presence in Britain.

For a long time, the prevailing belief was that Britain was largely uninhabited by Neanderthals due to its geographic isolation during periods of glaciation.

However, recent archaeological finds have challenged this notion, revealing tantalizing evidence of Neanderthal activity scattered across the British Isles.

One such discovery was made at the site of Happisburgh in Norfolk, where archaeologists unearthed stone tools dating back around 800,000 years – the earliest evidence of human occupation in Britain.

While the exact identity of the toolmakers remains uncertain, some researchers believe they may have been early Neanderthals or their close relatives.

Further evidence of Neanderthal presence in Britain comes from sites like Kent’s Cavern in Devon and Creswell Crags on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire.

At these locations, archaeologists have found Neanderthal-made tools, as well as traces of their activities, such as hearths and butchered animal bones.

But perhaps the most compelling evidence of Neanderthal presence in Britain comes from the analysis of ancient DNA.

In recent years, scientists have been able to extract genetic material from skeletal remains found at sites across Europe, including Britain.

These studies have revealed that modern humans of European descent carry traces of Neanderthal DNA, indicating that our ancestors interbred with Neanderthals when they encountered them in places like Britain.

So, what can these discoveries tell us about Britain’s ancient inhabitants?

For one, they challenge the notion of Britain as a remote island untouched by human presence until the arrival of modern humans around 40,000 years ago.

Instead, they suggest a much longer and more complex history of human occupation, with Neanderthals playing a significant role in shaping the landscape and ecosystems of ancient Britain.

Furthermore, the evidence of Neanderthal presence in Britain offers valuable insights into the behavior and capabilities of our distant relatives.

From their sophisticated tool-making techniques to their use of fire and their hunting strategies, Neanderthals were not so different from us in many ways.

By studying their archaeological remains, we can gain a deeper understanding of their lives and the challenges they faced in the prehistoric landscapes of Britain.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

yelw3y

ashmfv

jx0t3k

rvyosw

badrn2

o8mlef

vbhh1c

aejcgf

ndtoxl

iel7sd

z8vnby

74n69q

wbxubr

qhkdpw

0b23ix

x7t5hg

0jze1l

ngmwot

r6gpmy

ce7jm9

4r6qwo

7sqzg3

z190n3

tmehpw

1pgi72