The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already expanded humanity’s vision further into time and space than ever before, giving a breathtaking sneak peek of the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the early Universe to date.

Now, NASA has just unveiled five more stunning full-color images captured by the most ambitious telescopes humanity has ever built.

“You ain’t seen nothing yet,” Gregory L. Robinson, James Webb Space Telescope Program Director, teased in the lead-up to the reveal.

And boy was he right! Feast your eyes on these incredible visions that are clearer and more detailed than we’ve ever seen them before.

If you’re not already mind blown, consider that this is just five days worth of images!! It’s a culmination of decades of hard work from many people around the world and it’s only the beginning.

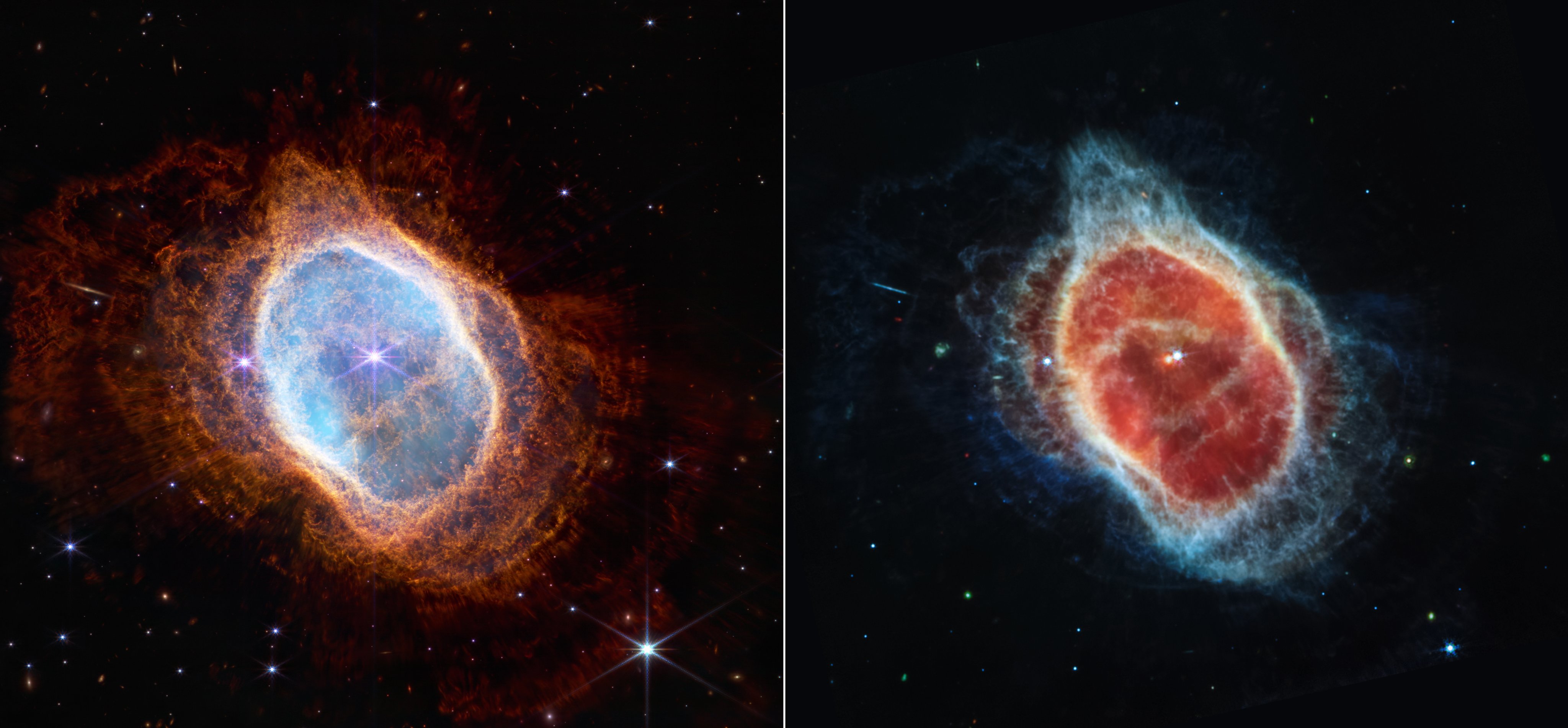

The Southern Ring Nebula

What you’re looking at here are spectacular waves of death from the Southern Ring Nebula – shells of gas shuddered off from dying stars.

The Southern Ring Nebula, AKA NGC 3132, is located around 2,500 light-years away and is a gorgeous, glowing blob in the southern constellation of Vela.

There are two stars in its center. The fainter one is a white dwarf; the collapsed core of a dead star that, during its lifetime, was up to eight times the mass of the Sun. It reached the end of its life, blew off its outer layers, and the core collapsed down into an ultradense object: up to 1.4 times the mass of the Sun, packed into an object the size of Earth. Although it still shines, it’s just from residual heat. Over billions of years, it will cool to a dark, dead object.

For the first time, JWST has been able to reveal that this star is cloaked in dust. The brighter star is in an earlier stage of its evolution, and will one day explode into its own nebula.

(NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI)

On the left, Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) reveals bubbly orange hydrogen from newly formed expansions as well as a blue haze of hot ionized gas from the leftover heated core of the dead star.

On the right, in the image captured by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), blue hydrocarbons form similar patterns to the orange in the previous image, because they gather on the surface of hydrogen dust rings.

This image shows for the first time that the dimmer star is surrounded by dust.

“Webb will allow astronomers to dig into many more specifics about planetary nebulae like this one,” explains NASA. “Understanding which molecules are present, and where they lie throughout the shells of gas and dust will help researchers refine their knowledge of these objects.”

To provide context about the new level of detail, here is Hubble’s view of the Southern Ring Nebula, taken in 1998.

(Hubble)

Read more about the image of the Southern Ring Nebula.

The Deep Field Image

We’ve already seen the deep field image of SMACS 0723, filled to the brim with galaxies frozen in time billions of years ago. Today, the Webb team provided some more insight into the image.

Read more about the Deep Field image.

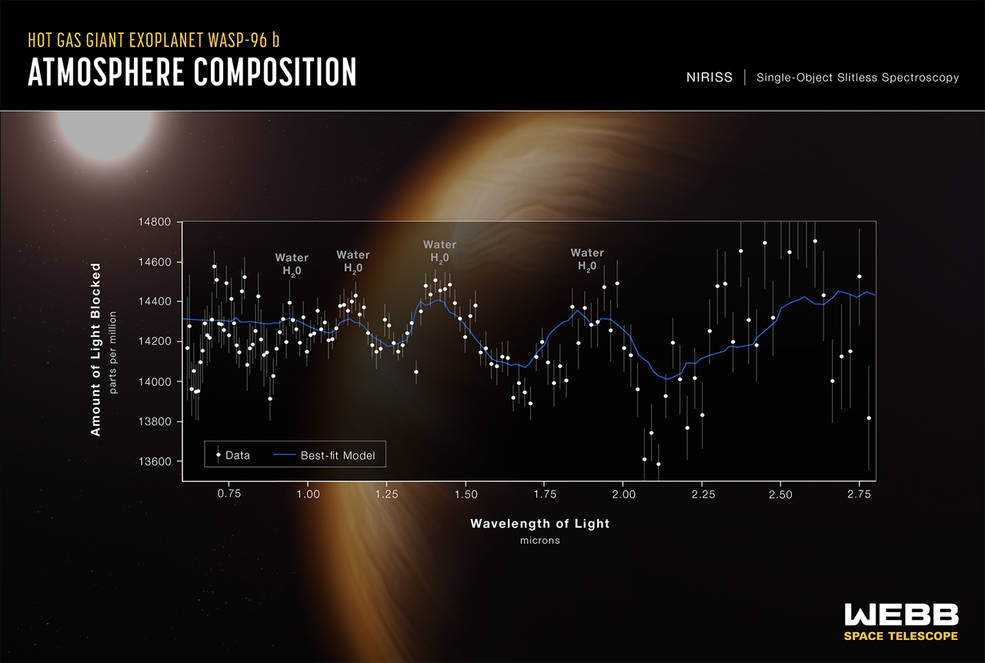

Exoplanet WASP-96b

One of JWST’s targets was exoplanet WASP-96b, a hot puffy world that’s so close to its star it has just a 3.5 Earth-day orbit. It’s whipping around a Sun-like star 1,150 light-years away.

WASP-96b has a mass less than half that of Jupiter and a diameter 1.2 times greater, so it’s a lot puffier than any gas giant we have in our Solar System – and a lot hotter, too, with a temperature higher than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (538 degrees Celsius).

What’s fascinating is that JWST has been able to detect evidence of clouds and haze in the exoplanet’s atmosphere, capturing “the distinct signature of water”.

(NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI)

By observing tiny decreases in the brightness of specific colors of light over a 6.4-hour period on June 21, JWST was able to reveal the presence of specific gas molecules around the planet. This is the most detailed observation of an exoplanet’s atmosphere we’ve ever received.

How does it work? When an exoplanet passes between us and its host star – what is known as a transit – a small, very small, amount of the star’s light ought to pass through the star’s atmosphere, if it has one. Scientists can look at the spectrum of that light to look for brighter or dimmer wavelengths from light that has been absorbed and re-emitted by elements in the atmosphere. This can tell us what those elements are.

What’s interesting is that previous observations suggested WASP-96b had a clear atmosphere, with no clouds. So we still have quite a bit to learn about this weird exoplanet.

This isn’t the first time we’ve detected water in an exoplanet’s atmosphere – the Hubble Space Telescope did this in 2013 – but Webb’s detection is faster and far more detailed, and only hints at the potential of what lies ahead for our understanding of alien worlds.

Read more about the WASP-96b observations.

Stephan’s Quintet

Stephan’s Quintet is a group of galaxies locked in a cosmic dance with collisions and new stars exploding into being (the red areas in the image below).

The new JWST image of Stephan’s Quintet is monstrously massive, covering an area of the sky one-fifth of the Moon‘s diameter (as seen from Earth) and containing more than 150 million pixels. It was constructed from around 1,000 image files – and it helps us understand how these dramatic galactic interactions shape galaxy evolution.

(NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI)

In the topmost galaxy in this image, NGC 7319, scientists identified the signs of material swirling around a massive black hole. The light energy it’s putting out from all the material it’s gobbling up is 40 billion times that of our Sun.

While five galaxies are in view, only four of them are actually close together – the one on the left, NGC 7320, is much closer to us at 40 million light years away, whereas the others are around 290 million light years away.

You can compare the JWST image to the 2009 Hubble view.

Read more about the image here.

The Carina Nebula

Last, but in no way the least, is the gorgeous Carina Nebula as we’ve never seen it before – complete with hundreds of brand new stars. This incredible image shows the edge of a nearby young star-forming region, also called NGC 3324.

The staggering detail in the infrared JWST image provides an amazing sense of depth and texture and there are many mysterious new structures to explore.

(NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI)

Known as the ‘Cosmic Cliffs’, the tallest peak in this image is a staggering 7 light-years high, with blue ionized gas steamed off it by intense radiation.

The top is where newborn stars are exploding into life and the stellar wind they produce pushes the orange-y gasses away, which in turn also ignites new stars or can snuff them out before they’re ever made.

What’s crazy is that we’re all composed of the same star stuff we can see in this image.

Read more about the Carina Nebula image.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth