The deepest infrared view of the Universe ever was just unveiled, and it’s even better than we could have imagined.

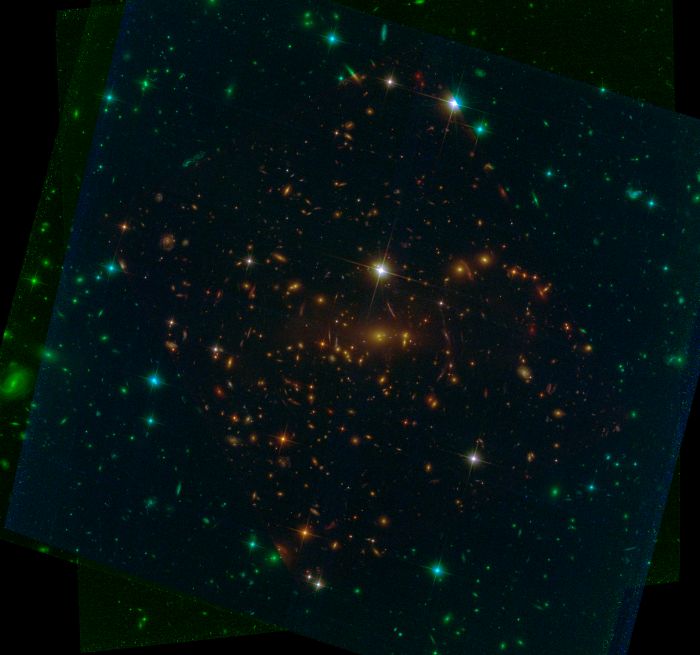

In a NASA livestream, US President Joe Biden released the first official image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), showing us an unprecedented new image of a region of space known as SMACS 0723 – a deep field into the distant Universe.

It’s the furthest back in time we’ve peered in the Universe to date, thanks to JWST’s impressive infrared capabilities and its giant mirror.

You can witness the image below in all its glory. We can’t stop staring at it:

For context: the image covers a patch of sky roughly the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone standing on Earth – and reveals thousands of galaxies.

“For the first time, we can see the details of these earliest galaxies, harbouring the first generations of stars to have ever formed in the Universe. These galaxies formed in a mostly dark universe, filled with neutral hydrogen gas, and very different to the cosmos we see today,” astronomer Cathryn Trott from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, who wasn’t involved in the research, told Scimex.

“This image captures the starlight from the earliest objects to have formed in the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang. This starlight is more than 13 billion years old, focussed toward JWST by the incredible bending power of a massive cluster of younger galaxies.”

Infrared is currently the best tool we have for peering into the very distant reaches of space. Webb is expected to see back further across space-time than we’ve ever been able to reach before, hopefully, to reveal new and key details about how the Universe began.

One tool for this is deep field imagery. Hubble took several deep fields, staring at a patch of sky for long stretches of time to collect the dimmest, most distant light possible.

For its first deep field, Webb has peered into a patch of sky called SMACS 0723, in the southern constellation of Volans. Hubble has also obtained some observations of this region, and Webb is expected to reveal even more.

SMACS 0723 imaged by Hubble using its infrared Wide Field Camera 3. (STSCI)

SMACS 0723 is a particularly good target for this sort of observation because there are massive clusters of galaxies in the foreground.

These act like a giant cosmic magnifying glass. Because of the immense mass, their gravity causes pronounced curvature of the space-time around them, with the effect of magnifying light from more distant objects.

Such gravitational lenses have previously yielded spectacularly detailed views into the distant Universe. In this image of SMACS 0723, totaling 12.5 hours of exposure time, we can see thousands of galaxies, many for the first time, including the faintest objects we’ve ever seen in infrared.

“We’ve got used to seeing Hubble Telescope images of distant galaxy clusters embellished with the distorted forms of even more galaxies beyond, magnified by the gravity of the foreground cluster,” said renowned Australian astronomer Fred Watson from the Australian Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources.

“But the first released image from the Webb telescope takes us into a breathtaking new regime of detail and depth, with galaxies at unprecedented distances now revealed. It’s a stunning taster of what is to come from this superb instrument.

“The Webb telescope’s capabilities are tuned to address some of the most profound questions in our exploration of the Universe. When did the first stars and galaxies form? How did they evolve? And what can we learn about the exoplanets orbiting stars in the Sun’s neighbourhood – including their potential for harbouring life?”

It’s been an epic journey for Webb, from the project’s commencement back in 1996, and one plagued with delays and setbacks.

To finally behold the first science images from this epic telescope is deeply wonderful, and incredibly satisfying – and just the first taste of the beauty and science to come.

“The quest for exploration is written in our DNA. This is why we climb mountains, we dive, we fly and we go into space. This image has put our feet into a new higher ground: we can see further than ever, we can see more than ever, we can be closer to our own Universe cradle,” Paulo de Souza, Dean of Research at Griffith Sciences at Griffith University in Australia, told Scimex.

“Everything we see in that image was set nearly 13 billion years ago. Right now, we could well have nothing left there. To know what was there now, we would need to look back there again in 13 billion years’ time. This image is a snapshot of a distant past.”

The single image was unveiled in a special early announcement at 6:15pm EDT (2215 UTC) on 11 July 2022 and is just the first of many we’re about to behold. Tomorrow morning, 10:30am EDT (1430 UTC) on 12 July 2022, NASA will drop the rest of JWST’s first photos one by one, in an epic press conference that will also be streamed live.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth