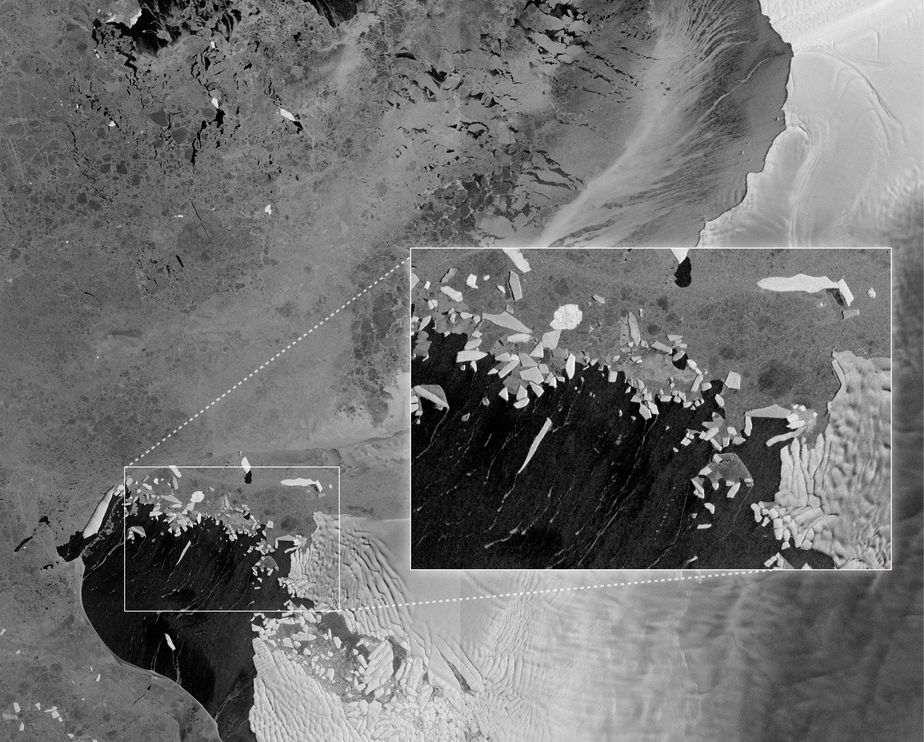

The calving front of the Thwaites ice shelf in Antarctica is seen on October 16, 2012. The melting shelf is causing the glacier behind it to collapse, a new study suggests.

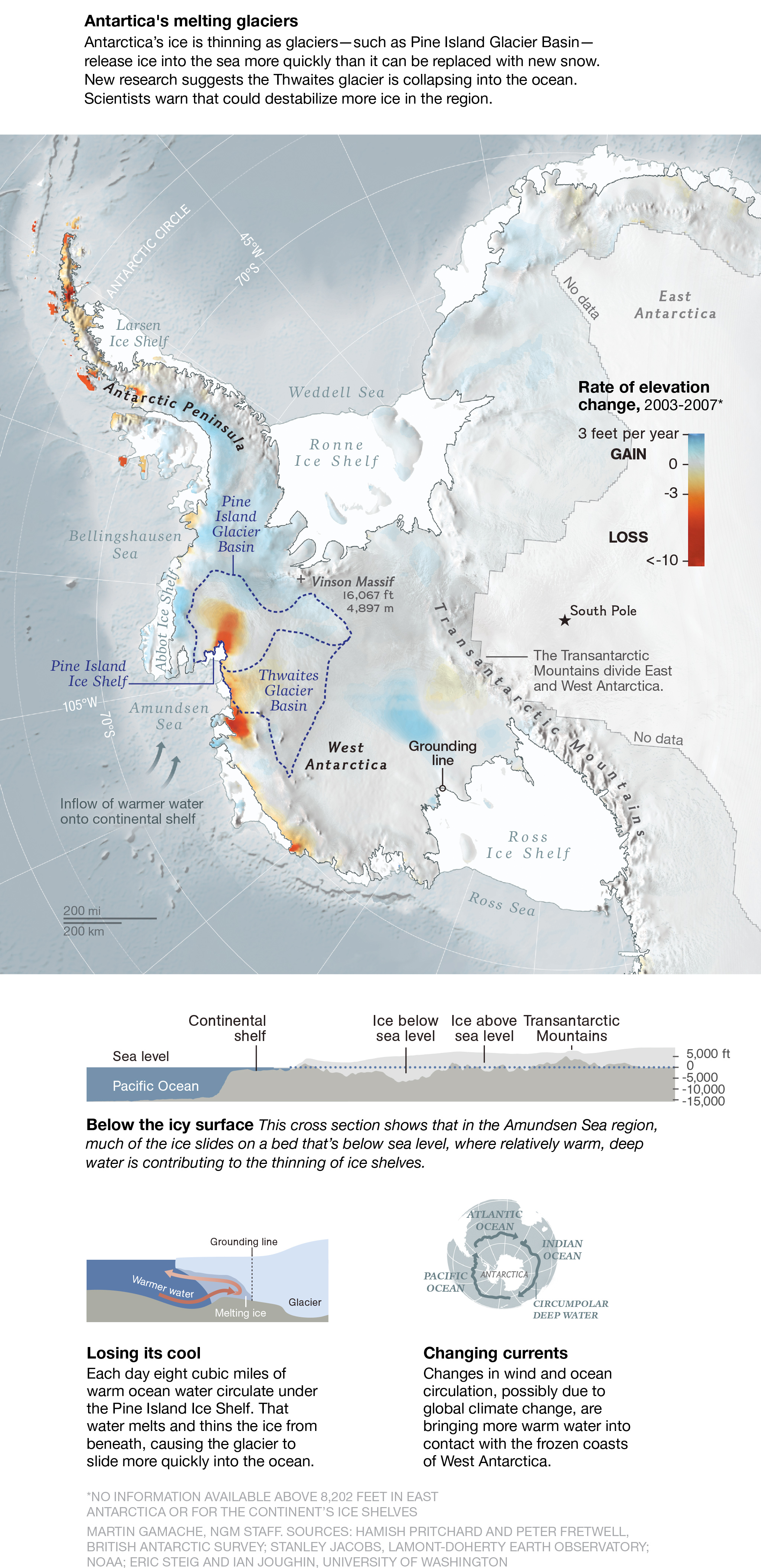

A massive glacier system in West Antarctica has started collapsing because of global warming and will contribute to significant worldwide sea-level rise, two teams of scientists warn in a pair of major studies released Monday.

Scientists had previously thought the two-mile-thick (3.2 kilometers) glacier system would remain stable for thousands of years, but new research suggests a faster time frame for melting.

A rapidly melting section of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet appears to be in irreversible decline and will sink into the sea, scientists at the University of California, Irvine and NASA reported Monday.

“This retreat will have major implications for sea-level rise worldwide,” said Eric Rignot, a UC-Irvine Earth science professor and lead author of a study to be published in a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

The study presents evidence, based on 40 years of observations, that six big glaciers in the Amundsen Sea “have passed the point of no return,” Rignot said on a Monday conference call with reporters.

The glaciers contain enough ice to raise global sea level by 4 feet (1.2 meters) and are melting faster than most scientists had expected, which will require adjusting estimates of sea-level rise, said Rignot, who is also a glaciologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

At their current rates of melting, he said, these glaciers would disappear in about two centuries, though “it could proceed faster or slower.”

More advanced computer modeling will be needed to estimate the rates, he said.

Crevasses are seen in the Thwaites glacier on October 16, 2012.

Computer Modeling Reveals Surprises

Some of that modeling is already under way and forms the basis for another study on West Antarctic ice melt released on Monday, which finds that a major glacial system in the region that was previously thought stable is collapsing.

Ian Joughin, who studies the physics of glaciers at the University of Washington, Seattle, says that the Thwaites glacier on Antarctica’s Amundsen Sea was thought to be “stabilized for a few thousand years.”

But “what we have shown is this glacier is really in the early stages of collapse,” says Joughin, lead author of a study published separately in the journal Science on Monday.

If the whole glacier system melts, Joughin says, it would raise global sea levels about 24 inches (60 centimeters), he adds. The process will take a while, roughly 200 to 900 years, Joughin and colleagues estimate, depending on how fast temperatures rise and how much snow falls in the area.

Richard Alley, a professor of Earth sciences at Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, who was not involved in either research project, says both are important. The data from Rignot’s group is consistent with the computer modeling by Joughin’s group, he says.

Next, the work of both teams needs to be confirmed by other models, he adds.

“But these results are sobering,” he says, “even the possibility that we have already committed to three-plus meters of sea-level rise from West Antarctica will be disquieting to many people, even if the rise waits centuries before arriving.”

Alley adds that the scientists avoided simulating “a worst-case scenario” of loss of all ice from Antarctica.

Icebergs that appear to have broken off Thwaites glacier spread across Pine Island Bay.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA

Unstable Ice

Rignot says that once the six glaciers near the coast melt, it is possible that the rest of the ice in West Antarctica could eventually follow. As a result of this new evidence published in Geophysical Research Letters, forecasts for global sea-level rise will likely need to be adjusted.

Joughin says that the collapse of the Thwaites glacier in particular could endanger much of the rest of the huge West Antarctic Ice Sheet, since the systems are connected.

“Imagine trying to take out part of a building and expecting the other half to keep on standing,” he says.

If the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet did melt, sea level would rise 11 feet (3.3 meters), according to previous research. (See “Rising Seas” in National Geographic magazine.)

Joughin says the breakup of the Thwaites glacier will resemble mechanical failure more than straight-up melting.

The ice will slide into the ocean, where it will break off and float away, adding to the volume of water in the sea.

A mixture of rock and frozen water has been holding the glacier back. Contrary to recent thinking, however, the glacier is no longer being held in place, Joughin says.

The ice shelf that has extended out over the ocean is melting, thanks to warmer temperatures, and that has decreased the friction that has held the glacier behind it in place. As pieces of the shelf break off, more of the ice behind it slides forward.

“It’s a little like how you get more flow out of a thicker hose than a thinner hose,” says Joughin, referring to an acceleration of the glacier sliding into the ocean.

Scientists had previously thought that a sill of bedrock, a vertical rock formation under the ocean, was holding back the advance of the glacier like a dam. But the work of Joughin and team suggests melting has greased the way over the rock.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth