Who built Göbekli Tepe and what is at this ancient site in Turkey? These ancient Turkish ruins contain the oldest temple in the world. It is also the world’s oldest archeological site and was created by an ancient Turkish civilization. To find out more about Göbekli Tepe’s age and use, let us explore the topic a bit deeper.

An Exploration of the Oldest Archeological Site, Göbekli Tepe

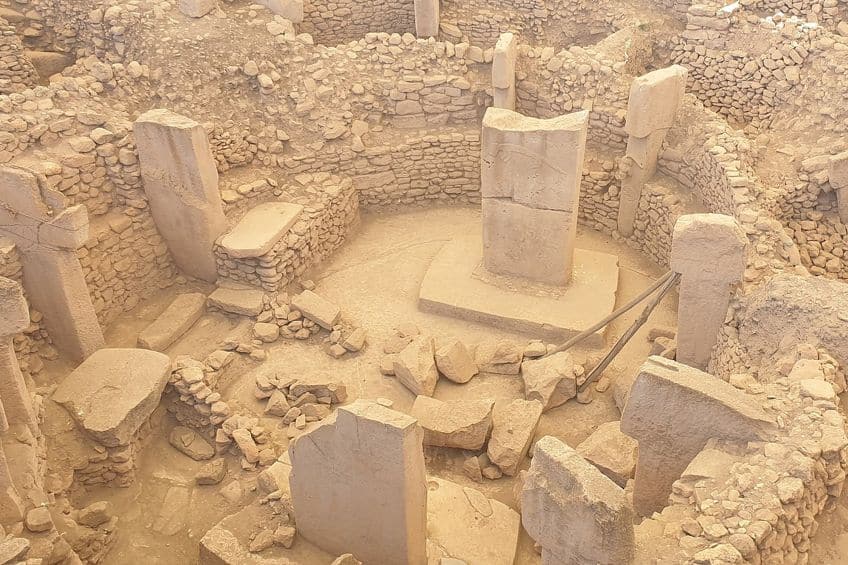

Göbekli Tepe is a Neolithic-era archaeological location situated in Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Region. The site, which dates to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, between about 9500 and 8000 BCE, is comprised of a number of huge circular formations sustained by massive stone pillars – the earliest known megaliths in the world. A number of these pillars are elaborately adorned with figurative human-like features, clothes, and wild animals, offering archaeologists unique insights into prehistoric iconography and religion.

A Brief History of the Oldest Temple in the World

| Architect | Ancient Turkish civilization |

| Date | c. 9500 BCE |

| Materials | Stone |

| Function | Temple |

| Location | Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey |

Göbekli Tepe was constructed and populated during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period of Southwest Asia. This era, which began at the close of the last Ice Age, represents the origins of village life, providing the world’s oldest proof of permanent human communities. Historians have long connected the emergence of these communities to the Neolithic Revolution – the shift from hunter and gatherer to agriculture producer, yet they differ in opinion on whether farming drove populations to settle down or settling drove individuals to take up farming. The discovery of these ancient Turkish ruins has added to this debate.

Regardless of its title, the Neolithic Revolution was not a sudden change but a drawn-out process that varied from one region to the next.

Aspects of village life developed in some locations as early as 10,000 years before the Neolithic, and the shift to agriculture would take thousands of years, with varying rates and paths in the various regions. The people of Göbekli Tepe were hunter-gatherers who augmented their diets with early kinds of farmed grain and lived in settlements for at least part of the year, based on the evidence found at the ancient site in Turkey. Mortars, pestles, and grinding stones, discovered at the world’s oldest archeological site have been studied, indicating extensive cereal processing. Archaeozoological data suggests “large-scale gazelle hunting” between the midsummer period and fall.

Location and Discovery of the World’s Oldest Archeological Site

Göbekli Tepe is situated in the Taurus Mountains’ foothills, overlooking the Harran plain and the Balikh River. The site is actually an artificial mound located on a flat limestone plateau that is linked to the adjacent mountains by a small promontory to the north. The ridge dips rapidly into steep cliffs in all other directions. Göbekli Tepe, like most Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in the Urfa region, was erected on a high elevation on the side of the mountains, affording it both a broad view over the plains below and clear views from the plain. Its position also provided the builders with easy access to raw materials: the limestone bedrock from which the structure was constructed, as well as flint for making tools to process the limestone.

Discovery

In the 1960s, anthropologists from Istanbul University and the University of Chicago examined – and disregarded – Göbekli Tepe. They visited the hill as part of a wide study of the area, found some broken slabs of limestone, and concluded the mound was merely an old medieval cemetery. Karl Schmidt was conducting his own study of ancient sites in the area in 1994.

He chose to visit the stone-littered mountaintop after noticing a passing mention of it in the University of Chicago researchers’ paper. Unlike those before him, he knew the area was special from the moment he saw it.

Initial Excavations

The oldest uncovered structures at Göbekli Tepe were erected around 9500 BCE, at the end of what was then the Neolithic era, according to radiocarbon dating. The site was substantially extended in the early ninth millennium BCE and was used until approximately 8000 BCE, or maybe somewhat later. There are indications that when the Neolithic constructions were deserted, smaller populations returned to dwell amid the ruins. Schmidt assigned the site to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period based on the stone tools discovered there. Due to methodological difficulties, determining its exact chronology took longer. The researchers discovered pillars organized in circles as they went further down. Schmidt’s team, on the other hand, discovered no evidence of a settlement: no hearths for cooking, homes, or rubbish pits, and no clay fertility figures that litter other sites of similar age. Archaeologists did, however, discover evidence of tool use, such as stone blades and hammers.

The Significance of Göbekli Tepe

It is remarkable not just because it is the first example of monumental construction made by an ancient Turkish civilization, but also because it has the potential to revolutionize our knowledge of early human history. Göbekli Tepe is also important in terms of preservation. The people who built the buildings purposefully buried them beneath several meters of earth, which served to shield them from the weather and maintain them in their original form for thousands of years.

Archaeologists have been capable of researching the buildings in great detail as a result of gaining fresh insights into the lives of early humans.

Technology and Culture

The site is made up of a sequence of circular and oval-shaped buildings composed of massive standing stones, some weighing several tons. These constructions are ornately carved with animals and other motifs. The sheer size and intricacy of the buildings, as well as the skill of the carvings, indicate that the builders were capable of intricate organization and social collaboration. This is evidence of technology that was more advanced than we expected from that era as well as indicative of huge cultural development. Such enormous and intricate constructions would have necessitated extensive social organization and collaboration, implying that the individuals who constructed Göbekli Tepe had already evolved complex social systems and cultural practices. The community rituals and meetings that took place at this location would have contributed to the strengthening of social bonds and similar cultural values, providing the groundwork for the formation of more sophisticated civilizations.

Agriculture

The significance of Göbekli Tepe stems from the fact that it undermines the widely held belief that the development of agriculture was the driving factor behind the rise of civilization. Before its discovery, it was thought that people only started to settle down and form sophisticated communities after developing agriculture. The creation of Göbekli Tepe, on the other hand, demonstrates that complex communities may have flourished before the advent of agriculture.

Some researchers suggest that religion, instead of agriculture, may have been the spark for the rise of civilization.

Religion

In the ancient world, Göbekli Tepe is said to have been a sacred religious center. The structures featuring the carved animal motifs were most likely utilized for communal rites and celebrations, and their exquisite ornamentation implies that they had ceremonial or religious significance. Göbekli Tepe demonstrates that early religious rituals were far more intricate and nuanced than previously thought. Before the discovery of Göbekli Tepe, it was assumed that individuals started to participate in elaborate religious rites only after agricultural practices had been developed and the foundation of established communities. The presence of such an intricate religious center, on the other hand, implies that religious ideas and rituals were an integral feature of early human communities, even before agriculture.

The Structure of Göbekli Tepe and Found Artifacts

Archaeologists dispute how much labor was required to build the site. Schmidt claimed that the process of extracting, transporting, and constructing tons of massive, monolithic, and practically uniformly well-prepared limestone pillars was beyond a few people’s abilities.

Utilizing Thor Heyerdahl’s tests with the moai of Rapa Nuias a guideline, he calculated that just moving the pillars required hundreds of laborers.

Building of the Structure

Based on these tests, one moai on the scale of a pillar from Göbekli Tepe would have required 20 workers a year to chisel and around 70 workers to transport 15 kilometers. These estimations support their conclusion that the site was erected by a vast, non-resident labor force that was compelled or persuaded to work there by a much smaller religious elite.

Some believe that 10 people would have been capable of moving the pillars with ropes and a lubricant such as water, similar to the techniques utilized to build other structures such as Stonehenge. Tests at Göbekli Tepe reveal that all of the structures now visible could have been erected in less than four months by around one or two dozen people, accounting for time spent mining stone, collecting, and preparing food. These labor estimates are estimated to be within the capacity of a single Neolithic family or village group. These also correspond to the number of individuals who may have comfortably occupied one of the structures at the same time.

Pillar Iconography

The stone pillars at Göbekli Tepe’s enclosures are T-shaped, as are those at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in the vicinity. However, unlike the other sites, several of the pillars have been carved, usually in low relief but occasionally in high relief. The majority of the carvings represent animals, primarily snakes, foxes, wild boars, gazelles, wild sheep, vultures, and ducks. The creatures, as far as can be determined, are male and usually represented in an aggressive stance. Abstract forms, typically a horizontal or upright ‘H’ sign, but occasionally disks and crescents, are also portrayed.

Human depictions are uncommon; however, pillar number 43 in the D enclosure features a headless person with an erect phallus.

The pillars’ “T” form, on the other hand, is anthropomorphic: the shaft is the torso, and the tip is the head. This is corroborated by the fact that, in addition to animal reliefs, several pillars include representations of loincloths, arms, and hands. The two center pillars held a prominent role in the enclosures’ symbolic architecture. Enclosure D has human-like figures with a belt, arms, and a piece of fabric covering the genitals. The gender of the people represented is unclear, while Schmidt speculated that they are two men since the belts they wear are a masculine trait at the time. There is just one distinct portrayal of a female, who is displayed naked on a slab.

The buildings at Göbekli Tepe have also produced a number of small engraved stones that cannot be assigned to a certain time. The iconography of these artifacts is comparable to that of the pillars, with animals, and also humans, especially men, depicted. A fragmented totem-like relic was discovered in one of Layer II’s constructions. It measures 192 cm high and 30 cm in diameter when reassembled. It portrays three figures: a predatory animal with a missing head and a human’s arms and neck; a second headless character with human arms, most likely a male; and a third creature with an intact head. Snakes are engraved on both sides.

Meaning of the Sculptures and Pillars

Based on analogies with other shrines and communities, Schmidt theorized on the beliefs of the tribes who built Göbekli Tepe. He hypothesized shamanic rituals and proposed that the T-shaped pillars depict human figures, potentially ancestors, although he believed that a fully formed belief in deities wasn’t established until later, in Mesopotamia, and was connected with enormous palaces and temples. This is consistent with an old Sumerian belief that agriculture, livestock farming, and textiles were introduced to humanity by Annuna deities from the holy mountain Ekur, which was populated by Annuna gods, extremely ancient deities without specific names.

Schmidt recognized this narrative as a prehistoric oriental myth that retains a fragment of Neolithic memory.

The animal and other representations clearly show no evidence of coordinated violence, since there are no portrayals of hunting expeditions or injured animals, and the pillar carvings usually overlook the usual wildlife on which the community depended. Building on Schmidt’s view of round enclosures as sanctuaries, some historians interpret the Göbekli Tepe imagery as a cosmogonic map that would have linked the local population to the surrounding terrain and the universe.

Significance of the Site’s Tools

Flint blades, stone hammers, scrapers, and chisels, are among the tools discovered at Göbekli Tepe. The individuals who created the site were experienced in dealing with stone and had developed methods for precisely shaping and cutting it. One of the most famous tools discovered at the site is a T-shaped stone hammer, which is supposed to have been used to shape the gigantic stone pillars. The hammer is composed of diabase, a strong metamorphic rock, and has a smooth texture, indicating that it was heavily used.

Additional tools discovered at the site include flint blades for carving and cutting, as well as scrapers for smoothing and shaping stone surfaces. Several of these items were discovered near the stone pillars, indicating that they were utilized in the site’s construction. These tools shed light on our predecessors’ amazing abilities to produce complicated structures and artistic pieces, as well as provide crucial insights into the technological and artistic achievements of early human communities.

Theories and Debates Around the Ancient Site in Turkey

The hill on which Göbekli Tepe resides was considered sacred before archaeologists studied it. The idea that the site was exclusively cultic and not inhabited has also been questioned by the proposal that the buildings served as enormous community residences, akin in some respects to the large plank houses of North America’s Northwest Coast with its spectacular house pillars and totem poles.

It is unknown why the old pillars were buried every few years to be replaced by newer stones as components of a smaller, circular ring inside the previous one.

Purpose

The actual purpose of Göbekli Tepe is still being debated by archaeologists and historians. Schmidt hypothesizes that Göbekli Tepe served as a religious or ceremonial center, maybe for communal assemblies, rites, or sacrifices. Another theory suggests that Göbekli Tepe was a political or social hub, potentially functioning as a meeting point for many clans or tribes in the area. The huge area of the site, as well as the presence of several enclosures and buildings, provide weight to the hypothesis that it was utilized for more than simply religious purposes. Some scholars say it was an agricultural location, with the stone pillars functioning as markers or fertility symbols for the adjoining fields.

A perspective that is more in alignment with what is understood about other significant Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites, where the ceremonial and secular functions coexist, has recently replaced the interpretations of Göbekli Tepe as a provincial ceremonial hub where tribal populations would occasionally converge. The subsequent discovery of household buildings and rainwater collection systems, for instance, has necessitated a reworking of the “oldest temple in the world narrative”.

Theories of Who Built Göbekli Tepe

What do we know about the people who built this ancient structure? The individuals who built Göbekli Tepe were most likely hunter-gatherers who resided in the area during the Paleolithic-Neolithic transition. Much is unknown about the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe, and their culture and manner of life are still being researched and debated by archaeologists and historians. According to one interpretation, those who constructed the site were part of a broader network of groups with comparable cultural and religious activities, however, the individuals who constructed Göbekli Tepe lived during a period when the region had few, if any, permanent civilizations, making it impossible to tell which other cultures they were associated with.

Another theory suggests that the people who built the ancient site in Turkey were able to achieve such extraordinary technological and artistic achievements as a result of a change in their way of life, from a nomadic hunter-gatherer existence to a more settled, agricultural one.

The Impact of the Discovery of the Ancient Turkish Ruins

The discovery of Göbekli Tepe has altered the timeline of human civilization, revealing that an ancient Turkish civilization was capable of creating complex buildings and engaged in symbolism and religious activities considerably earlier than previously assumed. This has caused us to reconsider our notions regarding the development of civilization. Göbekli Tepe’s discovery has also offered new information on the shift from hunter-gatherer tribes to established, agricultural communities. The discovery of Göbekli Tepe has also inspired renewed enthusiasm for the research of early human technology and culture, leading to new discoveries and perspectives into the development of human civilization.

As of yet, we have many questions still surrounding this ancient site in Turkey. However, due to Göbekli Tepe’s age, we are assured that whatever we learn in the future is bound to change our current understanding of human history. When it does, we will have gained a deeper insight into the way we lived, the religious beliefs we followed, and the technologies that helped pave the way for future civilizations.

What Is Göbekli Tepe?

Göbekli Tepe is an ancient site located about 16 kilometers northeast of Anlurfa, a historic city in southeastern Turkey. While this neighboring city has a strong religious history, it was uncertain how far back religion went in this region until the discovery of Göbekli Tepe. It was also designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. What is astounding is that apparently the Neolithic worshippers managed to start organizing themselves, quarry, and transport these 16-ton stone pillars up a hill, and assemble them in a circular, ritualized pattern, despite the fact that they lived in a world without metal, writing, or pottery, and at a period when archaeologists believed humanity had not yet gathered together to worship.

What Was Göbekli Tepe Built For?

There are various theories as to what the actual purpose of the ancient site in Turkey was. Some people believe that it is the oldest temple in the world and was used by various tribes as a place to stop on their travels. Others think that it was used for agricultural purposes. Another theory is that it was for housing. There is the possibility that it served multiple functions if compared to similar structures that were created elsewhere during the same period. For now, though, there are no definitive answers as to why it was built.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

ilgyss

ntviqa

5y2ix7