Microplastics are everywhere. These tiny plastic fragments can be found throughout the oceans, infiltrating the animals within it, the food we eat, and even our children.

The proliferation extends from the highest peak in the world to the beginnings of life itself. Even the remoteness of Earth’s polar regions offers no shelter from the storm – and new research helps to explain just where this endless inundation of microplastic debris is coming from.

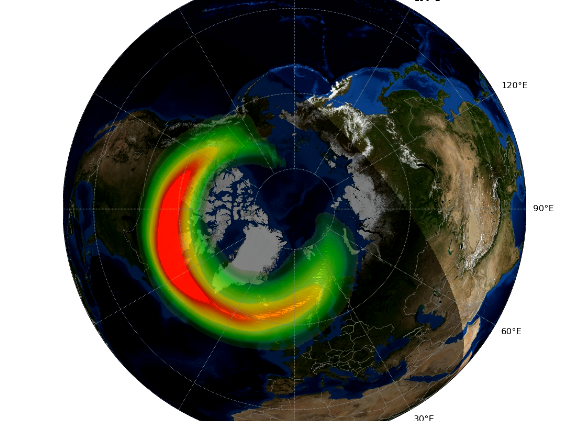

In a new study led by ocean pollution researcher Peter Ross from the Ocean Wise Conservation Association in Canada, scientists analysed the distribution of microplastics in the Arctic Ocean, sampling the contaminants in near-surface seawater at 71 sites across the European and North American Arctic, including the North Pole.

In addition to near-surface sampling – collecting microplastics at depths of 3 to 8 metres (10 to 26 ft) – the researchers also sampled at much lower depths in the Beaufort Sea to the north of Alaska and Canada, collecting microplastics at depths as low as 1,015 metres (3,330 ft) in the water column.

While it’s already known that microplastics have permeated the most remote reaches of the world, the mechanisms underlying their distribution and the scale of contamination remains unclear, the researchers say.

Here, the team used Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry to confirm an average Arctic-wide count of approximately 40 microplastic particles per cubic metre of ocean water, with the vast majority being microplastic fibres (92.3 percent), of which almost three-quarters (73.3 percent) were polyester.

But that’s not all.

“Particle abundance correlated with longitude, with almost three times more particles in the eastern Arctic compared to the west,” the researchers write in their paper, and in terms of the polyester pollutants, “an east-to-west shift in infra-red signatures [points] to a potential weathering of fibres away from source.”

In short, the researchers think that polyester fibres are delivered to the eastern Arctic Ocean from the Atlantic Ocean and possibly also via atmospheric transport from the south, breaking down into smaller pieces as they degrade and move to the west Arctic.

The culprit, the team suggests, is textile fibres in domestic wastewater, with polyester and synthetic fibres being shed from clothing when washed, before passing into waterways that transport the contaminants to the ocean.

According to the researchers’ estimates, a single apparel item can release millions of fibres during a typical domestic wash, and wastewater treatment plants can release over 20 billion microfibres annually.

“These estimates follow reports of large numbers of microfibres being shed by various textiles in home laundry, and a dominance of synthetic microfibres in municipal wastewater,” the authors explain.

“While further inventories will no doubt add to the source identification of Arctic MPs, we suggest that the combined, historical release of wastewater from Europe, the Americas and Asia, warrants additional scientific scrutiny.”

That’s putting it mildly. As Ross explains in a video from 2018, it’s imperative that we track where microplastic pollution is coming from, if we’re ever to have a chance of stopping this insidious threat.

“The more we look for microplastics in our environmental samples, the more we realise… we’re in a cloud of plastic dust,” Ross says. “Everywhere we look, we find microplastics… microplastics are everywhere.”

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth