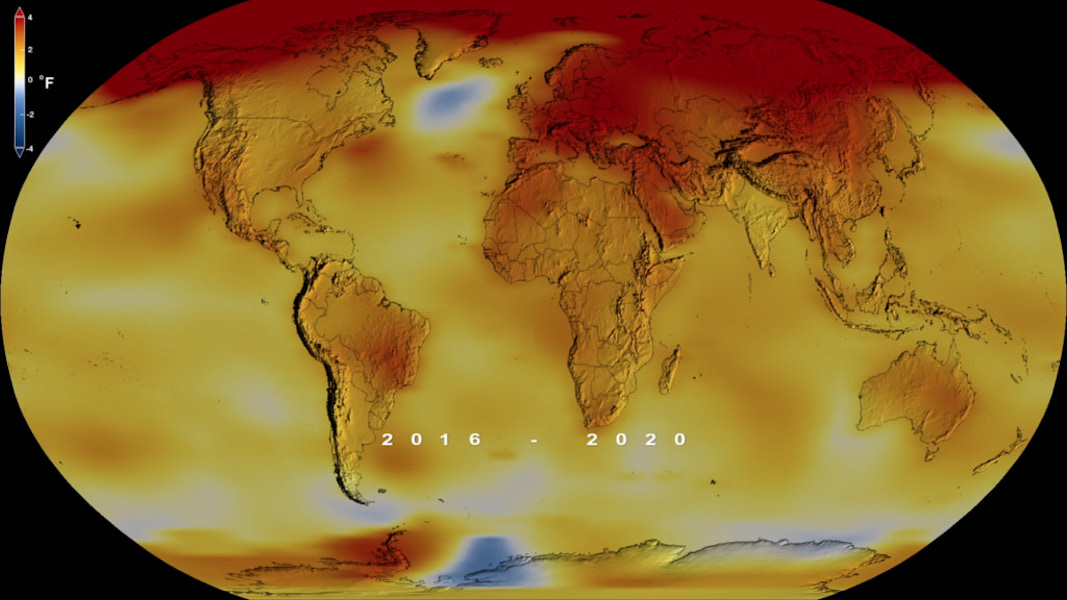

NASA announced Thursday that 2020 was likely the planet’s hottest year on record, edging out 2016 by one-tenth of a degree Celsius. The temperatures were close enough to fall within the scientists’ margin of error, so they considered it “a statistical tie.”

Average global temperatures in 2020 were 1.84 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) warmer than in the 30-year average between 1951 and 1980, NASA scientists found.

A second study of global warming conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found that 2020 was actually the second-warmest year ever, behind 2016, perhaps due to the fact that NOAA researchers compared the annual temperature average to the 100-year average between 1901 and 2000.

Still, the data may help explain why the climate crisis surged to new heights in 2020, particularly in the US.

Scientists can’t say whether an individual storm or fire was directly caused by climate change, since many factors contribute to each event. But experts agree that as the planet warms, weather becomes more extreme.

“The last seven years have been the warmest seven years on record, typifying the ongoing and dramatic warming trend,” Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said in a press release.

Extreme weather is linked to rising temperatures

It’s probably no coincidence that Earth’s hottest year (tied or not) was plagued by bizarre weather.

Bushfires raged through eastern Australia in January. In South America, the largest tropical wetland on Earth went up in flames. Typhoon Goni barreled into the Philippines with sustained winds of 195 mph (313 km/h), making it the strongest tropical cyclone landfall in history. A huge glacier broke off a Greenland ice shelf and drifted into the sea.

Research has shown that the changing climate is contributing to stronger hurricanes, more severe heat waves, larger and more destructive wildfires, and heavier rainfall that can cause flooding.

“Global warming won’t necessarily increase overall tropical storm formation, but when we do get a storm it’s more likely to become stronger,” Jim Kossin, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA, told The Guardian. “And it’s the strong ones that really matter.”

Some studies have linked the warming climate to the now-familiar arrival of the polar vortex at temperate latitudes. Rising temperatures could even be driving more severe thunderstorms and tornado outbreaks.

The US saw $US95 billion in climate disaster damages

No part of the US was spared a disaster last year.

Heat waves dried out the West and a polar vortex chilled the Northeast.

Wildfires in the Pacific Northwest and Rockies forced tens of thousands of people to evacuate their homes in late summer. Four million acres burned in California – more than double the previous state record. Fires killed at least 31 people in California, nine in Oregon, and one in Washington.

Colorado, too, saw three of the four largest fires in state history. The region hadn’t seen fires of that scale in 1,000 years, journalist Eric Holthaus reported.

At the same time, more hurricanes howled along the Gulf and Southeast coasts than in any other year in recorded history. Lake Charles, Louisiana didn’t have time to recover from one cyclone before the next one hit. Hurricane Laura ripped up homes with 150 mph (240 km/h) winds. Six weeks later, Hurricane Delta dumped more than 15 inches (38 cm) of rain.

The centre of the continental US, meanwhile, endured record storms, floods, and tornado swarms.

All told, the US had 22 weather and climate disasters in 2020 that cost the nation $US1 billion in damages or more – blowing by the previous annual record of 16 disasters in 2017.

The 22 billion-dollar disasters – seven linked to tropical cyclones, 13 to severe storms, one to drought, and one to wildfires – totaled $US95 billion in damages, according to NOAA.

No place to hide

Earth’s warming over time makes one thing increasingly clear: Soon, if not already, there will be no place to hide from the destructive consequences of humans’ climate-altering behaviour.

Extreme heat could make some regions across the central US, Middle East, and Australia almost unlivable in the summers. Scientists expect extreme storms and fires to get worse, too. All that could deal a severe blow to food production.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth