Where life might live beyond Earth

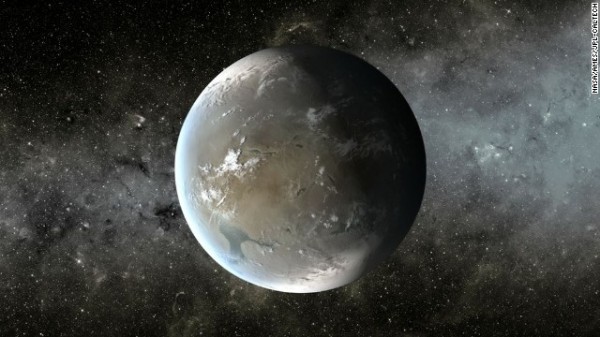

A team of astronomers announced April 17, 2014, that they have discovered the first Earth-size planet orbiting a star in the so-called “habitable zone” — the distance from a star where liquid water might pool on the surface. That doesn’t mean this planet has life on it, says Thomas Barclay, a scientist at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute at Ames and a co-author of a paper on the planet, called Kepler-186f. He says the planet can be thought of as an “Earth-cousin rather than an Earth-twin. It has many properties that resemble Earth.” The planet was discovered by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. It’s located about 500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus. The picture above is an artist’s concept of what it might look like.

HIDE CAPTION

Where life might live beyond Earth

Scientists announced in June 2013 that three planets orbiting star Gliese 667C could be habitable. This is an artist’s impression of the view from one of those planets, looking toward the parent star in the center. The other two stars in the system are visible to the right.

HIDE CAPTION

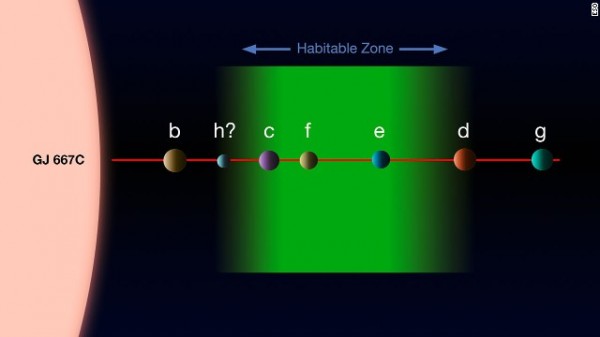

This diagram shows the planets thought to orbit star Gliese 667C, where c, f, and e appear to be capable of having liquid water. The relative sizes, but not relative separations, are shown to scale.

HIDE CAPTION

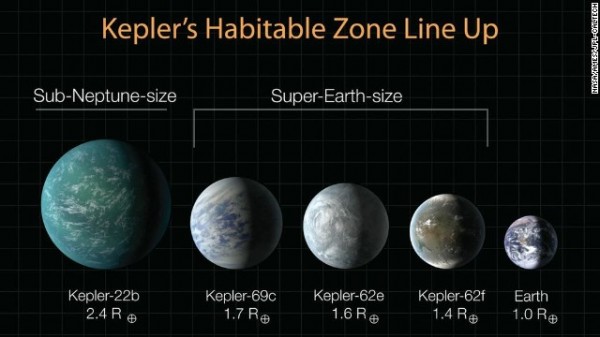

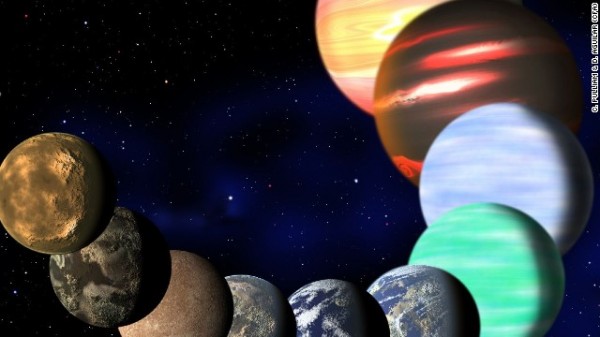

This diagram lines up planets recently discovered by Kepler in terms of their sizes, compared to Earth. Kepler-22b was announced in December 2011; the three Super-Earths were announced April 18, 2013. All of them could potentially host life, but we do not yet know anything definitive about their compositions or atmosphere.

HIDE CAPTION

This illustration depicts Kepler-62e, a planet in the habitable zone of a star smaller and cooler than the sun. It is located about 1,200 light-years from Earth in the constellation Lyra.

HIDE CAPTION

This illustration depicts Kepler 62f, a planet in the habitable zone of a star smaller and cooler than the sun, in the same system as Kepler 62e.

HIDE CAPTION

This diagram compares the planets of our own inner solar system to Kepler-62, a five-planet system about 1,200 light-years from Earth. Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f are thought capable of hosting life.

HIDE CAPTION

This artist’s illustration represents the variety of planets being detected by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft.

HIDE CAPTION

CNN) — Scientists looking for signs of life in the universe — as well as another planet like our own — are a lot closer to their goal than people realize.

That was the consensus of a panel on the search for life in the universe held at NASA headquarters Monday in Washington. The discussion focused not only on the philosophical question of whether we’re alone in the universe but also on the technological advances made in an effort to answer that question.

“We believe we’re very, very close in terms of technology and science to actually finding the other Earth and our chance to find signs of life on another world,” said Sara Seager, a MacArthur Fellow and professor of planetary science and physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Finding Earth’s twin, that’s kind of the holy grail,” said John Grunsfeld, an astronaut who helped repair the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009 and is now an associate administrator at NASA.

Strides in the search for life

Scientists have made stellar strides in the past few years alone.

“We already know that our galaxy has at least 100 billion planets, and we didn’t know that five years ago,” said Matt Mountain, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland.

He credited the work of the Kepler Space Telescope for these new discoveries. The planet-hunting Kepler probe, launched in 2009, finds planets by looking for dips in the brightness of a star as a planet transits, or crosses, in front of that star.

Kepler also found the first Earth-size planet that orbits in a star’s habitable zone, the area around a star where a planet could exist with liquid water on its surface.

The Kepler mission builds upon the stalwart Hubble Space Telescope, which launched in 1990 and was the first of its kind to be placed in space. As Hubble orbits the Earth, it allows scientists to peer back in time, into distant galaxies, and yields stunning images of the cosmos.

Hubble has helped shape our awareness of our planet’s place in an ever-changing universe.

The Earth, though 4.5 billion years old, is a newcomer, said John Mather, senior project scientist on NASA’s next-generation James Webb Space Telescope. It’s only about one-third of the age of the universe.

And our galaxy is ever-evolving, with “about five or 10 new stars being born per year in our Milky Way,” Mather said.

Planet hunters

Hubble’s astounding views come from a vantage point only 353 miles above our Earth.

n comparison, the James Webb telescope will be a whopping 930,000 miles from our planet. That’s close to four times the distance between the Earth and the moon.

Webb is set to launch in 2018.

Mountain, who is the telescope scientist for Webb, said scientists now know where every single star is within 200 light years of the Sun.

NASA’s assembled panelists said, if they follow this map of stars, they’re certain to find a multitude of new planets.

“Every star in the sky is a sun, and if our sun has planets, we naturally expect those other stars to have planets also, and they do,” said Seager. She said if someone looked up at a starry sky and wondered how many of the stars have planets, the answer would be “basically every single one.”

Some of a star’s light will shine through the atmosphere, said Seager, and the Webb telescope should be able to pick up gases from the planet that are imprinted on the atmosphere. While the Webb telescope wasn’t designed to find signs of life on another planet, it can spot biosignature gases — gases in the atmosphere produced by life.

Seager said, with the James Webb telescope, “we have our first chance, our first capability of finding signs of life on another planet. Now nature just has to provide for us.”

Spotting Earths

Finding small planets, ones the size of Earth, is challenging, in part because they produce fainter signals, said Dave Gallagher, director for astronomy and physics at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who likened it to spotting a firefly beside a searchlight.

That difficulty doesn’t dull the hunt for another Earth or signs of life.

NASA administrator Charles Bolden said he counts himself among the people who “are probably convinced that it’s highly improbable in the limitless vastness of the universe that we humans stand alone.”

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth