The oldest and thickest Arctic sea ice – dubbed the last Arctic ice refuge – is now thought to be disappearing twice as fast as ice in the rest of the Arctic Ocean.

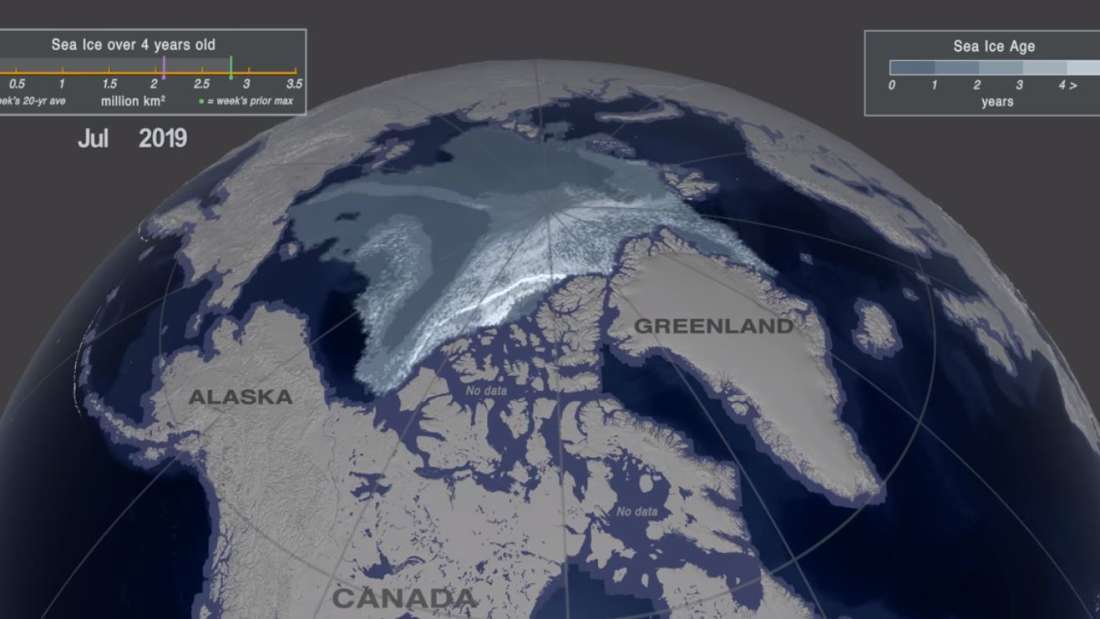

A new time-lapse video (below), created by the American Geophysical Union, shows the age of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean north of Greenland since 1984, shortly after reliable satellite observations began.

As you can clearly see, the once-robust region of old sea ice has changed dramatically over the past few decades, becoming progressively younger and thinner as time passes.

The video is based on data from a new study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Previous research suggested that this would be the last place to lose its year-round ice cover. However, the new models show it’s declining twice as fast as ice in the rest of the Arctic.

The new research used satellite observations and atmospheric data to show how ice thickness in two sub-regions of “the last ice refuge” fluctuates by around 1.2 meters (4 feet) from year to year. However, it also details a total loss of 0.4 meters (1.3 feet) of ice thickness per decade, amounting to a loss of 1.5 meters (5 feet) since the late 1970s.

The change of prediction is because the ice is much more mobile than previously thought. Although the sub-regions are old, they are subject to powerful ocean currents and atmospheric winds that result in the older (and often thicker and more robust) ice flowing out of the region.

The behavior of sea ice is a fiddly thing. The extent and thickness of sea ice ebbs and flows throughout the year depending on the season. Furthermore, some sub-regions of the ice can fluctuate more than others.

“We can’t treat the Last Ice Area as a monolithic area of ice which is going to last a long time,” lead author Kent Moore, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Toronto in Canada, said in a statement. “There’s actually lots of regional variability.”

“Historically, we thought of this place as an area that just receives ice. But these results are teaching us that this is a dynamic area,” David Barber, an Arctic climatologist from the University of Manitoba in Canada who was not involved in the new study, commented on the findings.

The effects of this could be profound. Wildlife in the upper stretches of the Northern Hemisphere, from seabirds to polar bears, depends on sea ice for refuge, resting, nesting, foraging, and hunting. It even affects life on a microscopic level, as sea ice plays a crucial role in the transportation and distribution of nutrients to seawater.

So, if the sea ice collapses, the Arctic food chain will soon follow.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth