Herds of horses, bison and reindeer could play a significant part in saving the world from an acceleration in global heating. That is the conclusion of a recent study showing how grazing herbivores can slow down the pace of thawing permafrost in the Arctic.

The study – a computerized simulation based on real-life, on-the ground data – finds that with enough animals, 80 percent of all permafrost soils around the globe could be preserved through 2100.

The research was inspired by an experiment in the town of Chersky, Siberia featured on CBS News’ 60 Minutes. The episode introduces viewers to an eccentric scientist named Sergey Zimov who resettled grazing animals to a piece of the Arctic tundra more than 20 years ago.

Zimov is unconventional, to say the least, even urging geneticists to work on resurrecting a version of the now-extinct woolly mammoth to aid in his quest. But through the years he and his son Nikita have observed positive impacts from adding grazing animals to the permafrost area he named Pleistocene Park, in a nod to the last ice age.

Permafrost is a thick layer of soil that remains frozen year-round. Because of the rapidly warming climate in Arctic regions, much of the permafrost is not permanently frozen anymore. Thawing permafrost releases heat-trapping greenhouse gases that have been buried in the frozen soil for tens of thousands of years, back into the atmosphere.

Scientists are concerned that this mechanism will act as a feedback loop, further warming the atmosphere, thawing more soil, releasing more greenhouse gases and warming the atmosphere even more, perpetuating a dangerous cycle.

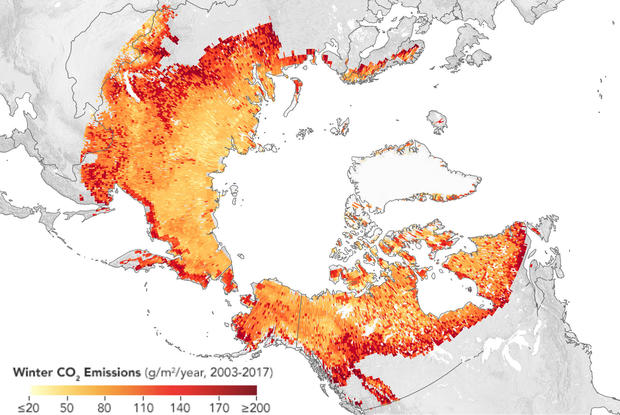

Last year their fears were confirmed when a study led by scientists at Woods Hole Research Center revealed that the Arctic was no longer storing as much carbon as it was emitting back into the atmosphere.

In winter the permafrost in Chersky, Siberia stays at about 14 degrees Fahrenheit (-10 degrees Celsius). But the air can be much colder, dropping down to 40 below zero Fahrenheit. Typically there is a thick blanket of snowfall in winter which insulates the soil, shielding it from the frigid air above and keeping it milder.

The idea behind Zimov’s on-the-ground Pleistocene Park experiment was to bring grazing animals with their stamping hooves back to the land to disperse the snow, compress the ground and chill the soil.

Turns out, it worked. The 100 resettled animals, across a one-square-kilometer area, cut the average snow cover height in half, dramatically reducing the insulating effect, exposing the soil to the overlying colder air and intensifying the freezing of permafrost.

In an effort to see what impact this method could have on a much larger scale, beyond the confines of Pleistocene Park, Christian Beer of the University of Hamburg conducted a simulation experiment. His team used a special climate model to replicate the impact on the land surface throughout all of the Arctic permafrost soils in the Northern Hemisphere over the course of an entire year.

The results, published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports, show that if emissions continue to rise unchecked we can expect to see a 7-degree Fahrenheit increase in permafrost temperatures, which would cause half of all permafrost to thaw by 2100.

In contrast, with animal herds repopulating the tundra, the ground would only warm by 4 degrees Fahrenheit. That would be enough to preserve 80 percent of the current permafrost though the end of the century.

“This type of natural manipulation in ecosystems that are especially relevant for the climate system has barely been researched to date, but holds tremendous potential,” Beer said.

CBS News asked Beer how realistic it is to expect that the Arctic could be repopulated with enough animals to make a difference. “I am not sure,” he replied, adding that more research is needed but the results are promising. “Today we have an average of 5 reindeers per square kilometer across the Arctic. With 15 [reindeer] per square kilometer we could already save 70 percent permafrost according to our calculations.”

“It may be utopian to imaging resettling wild animal herds in all the permafrost regions of the Northern Hemisphere,” Beer concedes. “But the results indicate that using fewer animals would still produce a cooling effect.”

Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the International Arctic Research Center in Alaska, agrees that snow disturbed and trampled by animal herds is a much less efficient insulator, but he has his doubts about implementing this idea.

“Unless the plan is to cover millions of square kilometers with horses, bison and reindeer, how could this possibly have any significant impact? I certainly would not call it ‘utopian’ to destroy permafrost lands as we know them by having these animals in the distribution and numbers required.”

Beer and his team did consider some potential side effects of this approach. For example, in summer the animals would destroy the cooling moss layer on the ground, which would contribute to warming the soil. This was taken into account in the simulations, but the cooling impact of the compressed snow effect in winter is several times greater, they found.

“If theoretically we were able to maintain a high animal density like in Zimov’s Pleistocene Park, would that be good enough to save permafrost under the strongest warming scenario? Yes, it could work for 80 percent of the region” said Beer.

As a next step, Beer plans to collaborate with biologists in order to investigate how the animals would actually spread across the landscape.

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable

Photographer Finds Locations Of 1960s Postcards To See How They Look Today, And The Difference Is Unbelievable  Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!

Hij zet 3 IKEA kastjes tegen elkaar aan en maakt dit voor zijn vrouw…Wat een gaaf resultaat!!  Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet

Scientists Discover 512-Year-Old Shark, Which Would Be The Oldest Living Vertebrate On The Planet  Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt

Hus til salg er kun 22 kvadratmeter – men vent til du ser det indvendigt  Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!

Superknepet – så blir snuskiga ugnsformen som ny igen!  Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth

Meteorite That Recently Fell in Somalia Turns Out to Contain Two Minerals Never Before Seen on Earth  Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer

Nearly Frozen Waves Captured On Camera By Nantucket Photographer  It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth

It’s Official: Astronomers Have Discovered another Earth